Review –The Secret History of Our Streets (Series 1)

This week’s episode is about people surviving despite the odds. Caledonian Road, which runs from Kings Cross into Islington, is shown to suffer for its connectivity to central London, which has left its inhabitants vulnerable to outside forces. Local, grimy and a thoroughfare to somewhere better, Charles Booth found it a place of sorrow and lack of hope where shopkeepers didn’t have the wherewithal to make a decent living. The map is described as being like an “x-ray that reveals the secret past that lies beneath the present”.

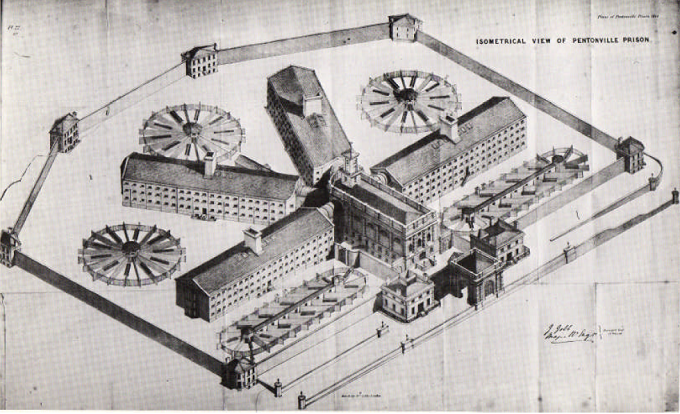

Like in the Reverdy Road episode to come in two weeks’ time, the programme has tracked down a descendent of the original land owner, the Thornhill family, who developed it in the early 19th century from hunting grounds to dwellings built to house the burgeoning middle-classes. We see that then, as now, the housing around the squares succeeded in following the “meticulous masterplan” to house the upscale professional housing – they are all coloured red (Middle Class). However, the land owner had no control over neighbouring developments and the soon to be built Pentonville Prison still “looms over” the Caledonian Road today (see in centre, to the right of Caledonian Road in Figure 1 and isometric in Figure 2). Evidently the problem isn’t the proximity to its inmates, but the massive bulk of building interrupting the street grid, a “fearsome void”* cutting it off from the continuity of the city. The subsequent development of Kings Cross station and its railways served to clear the neighbouring slums, but also to sever the lifeblood of the area’s arteries, leaving Caledonian Road globally connected and locally interrupted – effectively a peninsula east of the Kings Cross railway tracks . The smells and pollution of the railway lines were then mixed in with the noisy and noisesome cattle market and slaughterhouses, which were subsequently located to benefit from proximity to the railways.

Figure 1: Charles Booth Maps Descriptive of London Poverty, 1898-9. Courtesy LSE Archive.

The pair of images below, which show a map of the area coloured white on black (left) alongside a space syntax map of global accessibility, coloured from red (integrated) to blue (segregated), shows the Caledonian Road as a spine of high connectivity north-south, with relatively few connections running east-west. The Bemerton estate immediately to the west of the road (see detailed illustration below) is strikingly segregated from its surroundings and even more is the case with other estates in the area.

Figure 2: figure-ground map of Caledonian Road area c. 1980, courtesy UCL Space Syntax Laboratory.

Figure 3: Space syntax map of spatial accessibility (axial integration) for the Caledonian Road area c. 1980, courtesy UCL Space Syntax Laboratory.

Figure 4: zoom in on space syntax map of accessibility seen in figure 3

The Caledonian Road “had become the place to put the institutions needed by the city but not wanted in it” turning a central location into an undesirable address. The prostitutes taking advantage of the railway for commuting into work and for a ready supply of customers put the final nail in the coffin of the neighbourhood’s reputation. Yet the programme demonstrates that despite all this, a working-class community continued to develop its own identity, life reinforced through shops, pubs and small workshops – providing a living for the locals.

Figure 4: Isometrical perspective of Pentonville Prison, 1840-42, engineer Joshua Jebb. Report of the Surveyor-General of Prisons, London 1844. Illustration from Steadman, 2007

Fast forwarding to the 1950s, the Caledonian Road becomes a place for outsiders to settle and adapt to rapid change. Locals interviewed now reminisce that in those days, you knew your rogues and villains. If you were in the know, you could fence anything. Slum clearances and rehousing in modern blocks of flats in the 1960s and 70s were carried out to solve severe overcrowding. Whilst this didn’t necessarily result in the social problems seen in episode 1 of this series, the poor construction and maintenance meant that the “dream of modern living didn’t stand up to reality”. Along with the 1980s recession, the area deteriorated further, with many of its local shops closing down.

Despite this sorry tale the programme has a positive tone to it. The participants in the programme demonstrate a strong – even fighting – community spirit that has enabled them in the past to battle for a local park on derelict land and to subsequently fight against further railway developments in the late 1980s that would have led to the biggest building site in Europe. They successfully fought against the reputation of the area as supposedly not having a community – a ‘run down area needing redevelopment’. Its reputation as being full of drugs and prostitutes clearly missed the point that a substantial community lived and worked in the area. it is only recently that Caledonian Market finally shut down. The determination of the inhabitants to push British Rail back, to demonstrate that they were willing to fight against the might of the decision makers comes through very dramatically.

The residents of the area have saved the road, although it has moved upmarket at the Kings Cross end of the road, way beyond the reach of the inhabitants. The transformation of the area in just the past few years is shown to be the outcome of local people power along with opportunities seized by outside people recognising its potential. The community spirit is shown living on, with the episode ending with a sing-song in one of the local pubs.

Next week: the ultimate London bankers’ street – once a slum – Portland Road

Links

* Bullman, Hegarty and Hill: The Secret History of Our Streets, BBC Books.

Swensen, S., 2006. Mapping Poverty in Agar Town: Economic Conditions Prior to the Development of St. Pancras Station In 1866. London School of Economics, London, pp. 1-62. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/22539/

Steadman P. (2007) The Contradictions of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon Penitentiary, Journal of Bentham Studies, 1-31. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1324519/.

http://www.kxrlg.org.uk/group/history.htm

Edwards, M (2010) ‘King’s Cross: renaissance for whom?’, in (ed. John Punter) Urban Design, Urban Renaissance and British Cities, London: Routledge, 189-205. Eprint free at http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/14020

1 Comment